- Home

- Opiyo Oloya

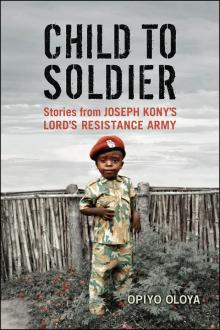

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army Page 2

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army Read online

Page 2

The two were chosen for several reasons. Foremost, of the seven informants, the two provided the most detailed information about their lives prior to, during, and after their service as CI soldiers. Jola Amayo’s stories are especially rich with details about her life prior to her abduction by the LRM/A, while Ringo Otigo provides more information about his life and times with the rebel army. Where one is silent on some aspects of his or her experience, the other tends to fill the void. For instance, Jola Amayo speaks at length about her combat involvement but hardly says anything about her developing sexual maturity in the bush. Almost out of the blue in the telling of her story, she talks about her son Otim. There is no preamble or introduction of Otim, just an abrupt mention of the child she had with another rebel fighter. I sensed that this is partly because, culturally, it is difficult for an Acholi woman to speak about her sexuality with a man who is not her husband (or her doctor). The other possible explanation goes back to the horrific nature of the experience that female LRM/A recruits go through in the bush as soldiers. Rather than press for an answer during these silent moments, I relied on the voice of Ringo Otigo, who was less reticent about speaking about his experience of sexuality in the bush, or rather the lack of it, and why he chose to be celibate.

Second, the two provided contrasts that went beyond gender. Ringo came from a family that had a ‘name’ in the community in that his late father was a doctor in Gulu Hospital. Although he grew up poor, he held to the sense that he came from a respectable family. It made him angry, he said, when someone showed a lack of respect for his widowed mother. Jola, meanwhile, grew up without any claim to social status beyond that conferred by being a member of a tight-knit family in a village in Acholiland. She was barely beginning to read and write when she was abducted by the LRM/A. Her maturing into a young woman happened in the bush as a combatant with the LRM/A.

Despite different socio-economic backgrounds, there are echoes of similarities in the experiences of Jola and Ringo as they made the transition from ordinary children to lethal child combatants. Both were stripped of their humanity at the beginning of their bush experiences, subjected to the most brutal treatment, and subsequently taught to fight for a cause they barely understood. Yet their experiences in the bush with the LRM/A were not identical.

The different standards by which the CI soldiers were treated dictated how they confronted and responded to challenges in the bush, and ultimately how they gained their freedom from the LRM/A. Even though she displayed combat bravery far superior to that of many male counterparts, and achieved the rank of second lieutenant, Jola Amayo and the other female CI soldiers were mostly under the immediate supervision of male officers. In contrast, as the son of a doctor, Ringo had received a good education and thus had the wherewithal to ‘speak’ with some measure and degree of self-assuredness, something that the other CI soldiers often lacked. With time in the bush, for instance, he acquired sufficient autonomy that he was allowed to conduct operations in faraway places without the direct patriarchal supervision of the top commanders. An LRM/A officer respected by those he commanded, he could make his own decisions at critical points. In essence, he became a trusted soldier whose judgment was relied on by other commanders.

When the LRM/A experiences of Jola and Ringo are examined side by side, there is a persistent sense that deep suffering seemed to dog the former over her entire time with the rebel army. She had to fight not only to be recognized as a fighter of worth within the male-oriented LRM/A structure but also to remain a nurturing mother to the children she bore in the bush. Where there were differences either in the stories told by these two or in their interpretations, the voices of the other five former CI soldiers provided additional perspectives. Payaa Mamit, for instance, was only in Grade Two when she was abducted by the LRM/A in September 1992; she attempted to escape but was recaptured, and her life was spared only by the intervention of LRM/A leader Joseph Kony. She became a mother in the bush, and when her LRM/A husband attempted to take away her child, she decided to escape from the LRM/A in September 2003.

Miya Aparo, the firstborn in a family of eleven children, was abducted at night on 13 April 1993 and spent the next eleven years as a child combatant with the LRM/A, returning home on 6 June 2002. After her homecoming, Miya Aparo tried her hand at different forms of small business. She now works as a counsellor for other former LRM/A returnees in Gulu.

Amal Ataro was the firstborn in a family of seven children. She was abducted by the LRM/A on 18 August 1994 and spent the next eleven years as one of the wives of LRM/A leader Joseph Kony, whom she said raped her when she went to live in his household in Sudan. According to her, all attempts by Sudan President Omar al-Bashir to rescue her from Kony failed because Kony repeatedly told the president that Amal was his sister. She gave birth to three children in the bush, all of whom were fatherd by Kony; the second child disappeared forever during an attack on the camp where she was then living. At the birth of the third child, she initially wanted to abandon it because ‘there was no food to eat and my breast milk was dry,’ but her older child insisted that she carry the baby. She, her firstborn, and the baby were rescued by the UPDF on 22 January 2005, after first being fired upon and miraculously escaping a hail of bullets that ‘tore my dress to shreds.’

Can-Kwo was abducted on a rainy afternoon in May 1996 and would spend the next eleven years with the LRM/A, returning home on 20 October 2007. He was badly wounded during his time with the LRM/A when his unit was bombed by the UPDF.

Lastly, Camconi Oneka was abducted on 15 August 2001 and spent the next three years as an LRM/A child combatant. He freely admitted killing other children after being ordered to do so. Never forgetting his home life, he attempted to escape numerous times. He finally succeeded after being wounded in a shootout with the UPDF, and was rescued on 15 July 2004.

Put together, the experiences of Jola and Ringo and the other five former CI soldiers serve powerfully to illustrate how the LRM/A used Acholi culture in recruiting, training, and retaining Acholi children in the war. Understanding this cultural link makes it clear that the almost two decades of horror visited upon children by the LRM/A were not a matter of bahati mbaya, the Kiswahili phrase for bad luck, but a deliberate, calculated, and focused effort to cause maximum dehumanizing violence against innocent young persons in order to control them.

The Cultural Link

When I met her for my first interview, I recognized that Miya Aparo’s life before her abduction seemed to echo my own childhood in Pamin-Yai where all twenty-six of us, children of three mothers and one father, lived in a polygamous compound.2 Miya and I shared a common Acholi heritage and spoke to each other in the Luo language. Our separate life journeys began in small rural villages, mine at Pamin-Yai village, west of Gulu town, and hers in Ajulu, in the Patiko region, northeast of Gulu town.

In my own case, I remember my childhood as an idyllic time. The children ate from the same dishes and slept together, girls in one house, boys in another; adults slept in the bigger house. While lunch and dinner were communal affairs, shared by everyone, a child could eat breakfast in any of the mothers’ houses. Often, I ate breakfast in the house of my First Mother, Mama Alici, my father’s senior wife. When not working or at school, we played dini-dini (hide and seek), spent time looking after cows, and occasionally went to hunt birds and small wildlife like anyeri (the edible rat) and apwoyo (rabbits). These were delicacies when smoked over the open-fire hearth and cooked in simsim (sesame) sauce, eaten with kwon bel (millet bread) The Acholi people believed that millet made them a hardy lot, strong and incredible runners and walkers. I was a fast runner.

Miya and I, though sharing a common herritage, were also different in many ways. She was barely able to read and write in any language, her education having been interrupted by the war, while I received a formal education and made a career as a lapwony (teacher). Also, I had not lived in my hometown for twenty-seven years and did not experience first-hand the war that started in 19

86 and caused the death of countless people while displacing others into internal refugee camps. What notion I had of what it meant to be an Acholi was not mediated by the war and its continuing social, economic, and cultural impact. I was a stranger now, a son of the land returning to a devastated home, albeit one who was keen to explore and make sense of what had led to the ruin of what he had once loved.

Miya Aparo, on the other hand, had been in the middle of the war and had experienced its devastation. After she was abducted from her home by the LRM/A in 1993, she lived the next eleven years as an active participant in the rebel army until the day she returned home in 2002. She was one of thousands of Acholi children abducted by the LRM/A over a period of two decades and turned into soldiers. She saw the LRM/A up close, lived in camps in southern Sudan, and waged a relentless fight against the UPDF. At thirty-one, Miya was not a child any more; however, she was a survivor insofar as she was alive and working to make a living in the community.

She began her compelling story in a quiet voice, taking me back to the day she was abducted by the LRM/A at age twelve. And the stories she told me were nothing like those I heard growing up in Pamin-Yai village, not far from where we were sitting. Listening to Miya, I found myself simultaneously replaying in my head my own childhood stories and comparing them to the gritty tales she was telling me. I heard her voice but I also heard my own. Ododo mera ni yoo (I have a story to tell) … So began many nightly stories told by our elders as we were growing up in Pamin-Yai, seventeen kilometres west of Gulu town. Storytelling was a part of the nightly ritual for Acholi children in those days, the way in which elders imparted life’s lessons.

In the dry season, after the harvest, we sat in a circle around wang-oyo, a bonfire created in the centre of the compound, listening to story after story. ‘I kare meno dong, Apwoyo ocito ka limo lawote, Twon-gweno’ (Once upon a time, the Hare went to visit his dear friend the Rooster) … That one was a favourite, always with the same sad ending where Rooster tricks Hare into believing that the dinner Hare was eating was one of Rooster’s legs when in fact the trickster had hidden one leg beneath his wing. When Rooster visits Hare a few days later, eager to have the favour returned, Hare gets his mother to cut off one of his legs and cook it for dinner. After dinner, and with Hare now bleeding to death, Rooster walks away on two legs. The moral of the story: Aporabot oneko Apwoyo (Imitation killed the Hare) …

In an instant, I am pulled back to the present as Miya Aparo narrates her life story:

When I was abducted, the first moment, it was around nine at night, and my life became difficult. When they came to abduct me, I was busy stone-milling. I had returned from school, fetched water from the well, and was stone-milling simsim paste. I was almost done stone-milling the paste. My mother was peeling wild yams to be eaten with the simsim paste that I had prepared …

I thought to myself, ‘How am I going to carry this entire load?’ They showed me how to carry everything; I needed to throw the bag on my back, wrapping its strings across my shoulder. The large cooking utensil needed to be tied and hung around my neck, letting it rest on the bag on my back. Then I had to put the two bucketsful of simsim on top of my head. A string was tied around the spout of the jerry can of sugar, and then tied around my neck, allowing it to hang on my side. The chicken in the polythene bag – there were four chickens – were brought for me to carry. I asked again, saying, ‘How am I going to carry this entire load?

We began walking and, before long, crossed the main road that ran behind our home. I fell down, my chest congested such that I could barely walk, my breathing laboured. The baggage had completely overwhelmed me, the one weight was pushing down on my chest, the other was pressing my shoulder, and meanwhile the one on my head was extremely heavy. I fell again and, this time, they came and began kicking me to get up. They hit my back with a machete, accusing me of refusing to carry the load, refusing to walk. The machete peeled some skin off my back. Someone came and said, ‘Look, the load is too heavy. This is a small child who cannot carry such a heavy load.’ I was crying. I was told that if I continued crying, I would be killed.

When I was growing up in Pamin-Yai, killing was not a part of our cultural experience. As with many Acholi, even the mention of killing brought fear of cen, the evil spirit that followed the killer and wiped out the killer’s family. Everyone feared the spirits of the dead. As children, we heard the story of how my father, Alipayo Oloya, left teaching in Gulu town to become a farmer in the early 1950s. He settled in the valley called Pa Min-Yai, which translates as ‘that which belongs to Yai’s mother.’ Flanked on one side by the Ayago River on its gentle flow towards the Nile River, and on the other side by Pamin-Yai Rock, a large outcrop that jutted defiantly out of the earth, the village was a few clusters of grass-thatched homes. The dusty narrow winding road that passed through the valley led to Gulu town to the east, Anaka centre, twenty kilometres to the west, and on towards Pakwach and Arua towns. But the road carefully skirted Pamin-Yai Rock. We children were told that the road builders did not want to incur the wrath of Min-Yai, the Mother of Yai and the spirit keeper of the rock. I never found out who Min Yai was, but many believed that she lived a long time ago in the foothills of the rock. Indeed, while playing or herding cattle, we occasionally found bits and pieces of broken pottery from long ago that lay buried there.

My parents often related the story of villagers taking bets on how long my father would last in his new home near the Pamin-Yai Rock. There were too many jok (vengeful spirits) around the rock, the villagers told my father. Some said the spirits came out at night, often in the shapes of beautiful women to lure away unsuspecting travellers to their demise. So strong was this belief that few dared to traverse the pathway that ran beside the rock at night. But my father lasted a week, then a month which turned into several years. When people saw that nothing happened to him and his young family, they began to settle and stay in the valley too. But often one heard the whispers, ‘The children of Oloya are protected by the spirits of Pamin-Yai,’ whispers that made me feel somewhat special as a child. Believing in the world of spirits was very much a part of Acholi culture. Miya Aparo was a part of that culture. So was I.

In working to gain insight into the role of culture in the LRM/A insurgency, I reflexively glimpsed continually at my own cultural upbringing in an Acholi village for context, meaning, and contrast to the narratives of the former child combatants. I discuss in more detail the duality of being a researcher as well as participant in chapter 1.

The term culture as I use it in this book is not only at the heart of the transformation of children into soldiers, but plays a crucial role in their daily struggles to make sense of the violence in which they have become a part, and, ultimately, to attempt to take some control of their lives within it. In taking the view that children do not come to war empty-minded, without some ideas and thoughts from prior enculturation about what violence and suffering mean to them, I borrow P. Alasuutari’s (1995) definition of culture as ‘a way of life or outlook adopted by a community or social class’ (25). This definition sees culture as the knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, needs, and motivations that shape how the child adapts to the cultural milieu in which he or she lives. In this sense, culture is the aggregation of shared values in a defined system from which individuals derive not only their identities but also their orientation to the world. There is an assumption of solidarity and unity of purpose among those who subscribe to those values.

The implicit premise of the culture perspective is that the given society clearly defines its value system and proscribes how individuals may live within it. Cultural life in Pamin-Yai village was simple in that it followed the seasons, cwii (rainy season) and oro (dry season). In the hot months, we harvested the crops and prepared them for storage. One of our favourite pastimes during this time was cooking layata abur (pit-roasted sweet potatoes). We dug sweet potatoes from the field and built fires in small pits, heating the earth until it was red hot; then we

threw in the freshly dug potatoes and covered the whole thing with a heap of fresh earth. The heated earth cooked the potatoes overnight, and in the morning we pulled out perfectly roasted and truly sweet tasting potatoes. We ate it with odii nyim (sesame paste).

When rain came, we worked hard in the field planting and tending to crops like maize, tobacco, cotton, and beans. This was also the time for trapping ngwen, the delicious flying white ants that came out after the first rains. We draped grass skirts around bye-agoro and bye-aribu (anthills). And after a downpour of rain, the worker termites opened the tiny ‘eyes’ on the anthills, allowing flying ants to flood the night or early morning sky with their silver wings flickering against the light. The grass skirt placed around the anthill acted as canopies to prevent the flying ants from escaping and flying away, forcing them instead into the pony, holes dug on the side of the anthills for just that purpose. All one needed to do then was to scoop up the fat succulent ants, eat some of them raw, and take some home to be ground into anying (meatballs) or dried and ground into the delicious oily odii ngwen (ant paste). I loved my odii ngwen mixed with a touch of honey and eaten with roasted gwana (cassava).

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army