- Home

- Opiyo Oloya

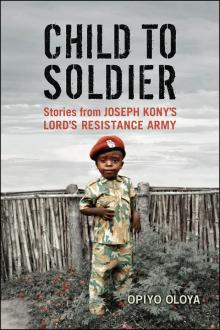

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army Page 6

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army Read online

Page 6

The Politics of Otherness in Post-Colonial Uganda

After Uganda’s independence in October 1962, using their ethnocultural affinities as a springboard, various state actors demonized other ethnicities as the source of Uganda’s problems. That is to say, the politics of ‘otherness’ as a by-product of the colonial policy of divide and rule were used to intensify ethnic resentment between groups classified by the colonials as ‘bantus’3 and those labelled ‘nilotics’4 or northerners. Early contact with Europeans promoted literacy in the south earlier than elsewhere in Uganda, and as a result southerners came to see themselves as superior to unsophisticated, illiterate, and ‘militaristic northerners’ (Jorgensen, 1981; Sathyamurthy, 1986). For their part, as one of the northern ethnicities, the Acholi viewed the southerners as luloka (laloka, sing.), those from across the river or lake or valley who formed the distinct other. Embedded in the concept of loka was contrasting group self-identity, which, for the Acholi, was succinctly expressed as wan (us) or expansively as wan luleb (we of the same tongue). Implicit in the notion of luloka was the untrustworthy, unprincipled, and dangerous other. For political mobilization and in determining who should get what, the wan luleb felt marginalized by those from loka whom they perceived as controlling much of the economy. The polarizing impact of culture and language further sharpened these ethnic self-interests in opposition to the interests of others. In fact, viewed through the internal lenses of each ethnic group, all other ethnicities are luloka, from the other side of the river, with the valley in between filled with mutual ignorance.

In 1966 a political power struggle became a crisis. Then Prime Minister Milton Obote, an ethnic Lango closely allied with the Acholi through the Luo language and culture, abrogated the constitution, which allowed for the sharing of power with Kabaka of Buganda as head of state. Obote swiftly used the military to oust Kabaka from his palace at Lubiri on the night of 24 May 1966. Artillery shelling of the palace set it on fire; Kabaka Mutesa, meanwhile, fled into exile in Britain. Ethnic Baganda felt strongly that Milton Obote had betrayed their king.

The 1966 constitutional crisis, also known as the Buganda Crisis, became a seminal event in the history of Uganda, with reverberations felt decades later. In the narrative of post-Idi Amin Uganda in the 1980s, with four political parties contesting the election, ethnicity mattered. Former president Obote led the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC); Paul Kawanga Ssemogerere, a Muganda from the south, led the Democratic Party (DP); Yoweri Museveni, a Munyankole from the west, led the new Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM); and Mayanja Nkangi, a Muganda from the south, led the monarchist Conservative Party (CP). All these leaders tended to play on ethnic fears of the other. In May 1980, for example, the politics of ethnic mobilization were in full gear, as demonstrated at a political rally I attended at Pece Stadium in Gulu (Oloya, 2005). The main attraction was the legendary commander of the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), Major-General David Oyite-Ojok. Though supposedly neutral as the commander of a national army that boasted a rank and file drawn from all ethnicities across Uganda, Oyite-Ojok, an ethnic Lango, was campaigning on behalf of former president Obote, who had returned from exile in time for national elections slated for 10 December 1980. Speaking in Luo, Oyite-Ojok warned, ‘Wan kom pe odok ii tim odoco. Ka owubolo kwir arac, ci wubino tingo matafali me yubo Lubiri’ (We will never go back into exile again. If you cast your votes carelessly, you will be forced to carry bricks for rebuilding the Lubiri).5 The mostly Acholi crowd roared back in appreciation.

Speaking on the eve of the first national election in almost two decades, Oyite-Ojok was reminding his audience that the contest was a choice not just between Uganda’s four political parties but also between the ethnicities of the leaders who led those parties. In his logic, voting for a party led by the wrong ethnicity, in this case, either the DP or CP, both led by Baganda, invited the potential for retaliation over the events of 1966. After all, at that point in post-Amin politics, barely a year after Amin was ousted from power, the leadership of Uganda had changed hands twice in bloodless coups. Professor Yusufu Lule, a Muganda intellectual, installed in April 1979 as the interim president in Amin’s wake, was himself ousted from power two months later, on 20 June 1979. Lule’s successor, Godfrey Lukongwa Binaisa, also a Muganda, fared little better, lasting eleven months until he, too, was removed from power on 11 May 1980. For Oyite-Ojok, whichever ethnicity won the December 1980 elections would decide who got what, when, and how. That was the game as he saw and played it.

Moreover, Oyite-Ojok was also tapping into the Acholi sense of alienation from the rest of Uganda since independence from colonial Britain. On 10 December 1980, several months after Oyite-Ojok made his statement in Pece Stadium, Milton Obote returned to power. However, Yoweri Museveni, who was a member of the powerful four-man provisional leadership, accused Obote of stealing the election (Avirgan & Honey, 1982; Clodfelter, 2002). Even as the newly elected Obote consolidated his power, Museveni retreated to the bush to form the Popular Resistance Army (PRA), later to become the National Resistance Movement/Army (NRM/A). The narrative adopted by the NRM/A in its insurgency against the ruling government was that of a populist uprising striving for a more democratic Uganda (Ngoga, 1998). Yet, in the ears of non-northerners, the NRM/A war was about not only the restoration of democratic ideals but also the overthrow of the northern hegemony that had begun with Milton Obote at the inception of nationhood in 1962, carried through the dictatorial years of Idi Amin, and resumed in full force with the return of Obote to power in 1980, inaugurating an era that became known as Obote II (Keitesi, 2004). To gain popular support in central, southern, and western Uganda, the NRM/A used propaganda to demonize northerners generally and the Acholi in particular as the enemies of a stable Uganda (Behrend, 1999; Nyeko & Lucima, 2002; Otunnu, 2002). In the south-versus-north politics of the day, the very survival of southerners was deemed to be at stake, depending on whether the NRM/A won or lost the war (Kutesa, 2006; Keitesi, 2004).

The Obote government’s bloody counter-insurgency campaigns against the NRM/A in Luwero in south-central Uganda, presided over by Major-General Oyite Ojok until his untimely death at the end of 1983 and later by two Acholi generals, Tito Lutwa Okello and Bazilio Olara-Okello, led to the genocidal killings of thousands of innocent Baganda. The atrocities committed against civilians in Luwero were mostly blamed on the Luo, especially Acholi soldiers in the UNLA (Behrend, 1998, Gersony, 1997; Mutibwa, 1992), although others finger Museveni’s NRM/A (Witzsche, 2003). This view of events would later have a dramatic impact on the Acholi population, which believed that the NRM/A had come to avenge the Luwero killings (Behrend, 1998). The gruesomely orchestrated counter-offensive by Obote and subsequently by General Okello notwithstanding, the NRM/A expanded the resistance front to the west, at the same time slowly marching towards the capital city of Kampala. In January 1986 the NRM/A, comprised partly of CI soldiers known as kadogos (the little ones), overran Kampala. Yoweri Museveni, a westerner, and regarded by Acholi as a laloka (from across the river), came to power.

Yet, in line with Appadurai’s notion of autochthony in which ethnicity is the perpetual stake in the belly of nationalism as a unifying ideal, where each ethnicity blames the others for conflict while ignoring its own role, it is common in Uganda’s post-independence political discourse to hear the aggressor described as the Acholi, the Baganda, the Banyankole, the Banya-Kigezi, the Teso, the Madi, the Lugbara, the Karimojong, and so forth. The simplistic, often repeated argument that Acholi society is warlike, for example, is used to explain the long record of the LRM/A rebels in abducting mostly Acholi children to be trained as CI soldiers (Cheney, 2007). This argument is based on the view of the Acholi as a ‘military ethnocracy’ (Mazrui, 1975; Doom & Vlassenroot, 1999) or a ‘militarized ethnicity’ (Mazrui, 1976, 250). E. de Temmerman (2001) puts it more bluntly when she writes, ‘The people of [the] northern region (the Acholi and Langi) were made into the country’s military elite’ (vii). The supposed bellig

erency of the Acholi, their characteristic martial attitudes and natural inclination towards violence, has been used to explain the role of the Acholi in the violent post-colonial history of Uganda (Gutteridge, 1969, 13; Ogunbanjo, 2002, 5).

The undertone of the same argument is discernible in the description of the war in Acholi since Yoweri Museveni came into power in 1986 as ethnic cleansing of the Acholi by vengeful southerners (Dolan, 2009, 153). But, when violence in post-colonial Uganda is viewed through the lenses of Appadurai’s autochthony, it cannot be attributed to the character of any particular ethnic group, or even deemed to be perpetrated along purely ethnic lines. Rather, a complex picture emerges in which Uganda’s numerous post-independence conflicts and violence tend to hint at ethnicity but not always be strictly based on it.

Indeed, as this book unfolds, I will suggest that in northern Uganda, where the war served different purposes for different entities including the government of Uganda, the LRM/A committed crimes against humanity not in defence of the Acholi people or Acholi interests, seen to be threatened by Museveni’s NRM/A, but against the Acholi themselves. It is my contention that the LRM/A is an opportunistic and predatory self-styled rebel movement that keenly exploited the chaos following the entry of the NRM/A in Acholi, and employed mass killings against the Acholi and other ethnic groups in northern Uganda to attempt to carve out a territory under its control with the leader Joseph Kony as the overlord. In the next chapter, I distinguish between the war led by Alice Auma Lakwena, which I characterize as an ill-fated, confused, poorly equipped, and spontaneous grassroots uprising to defend the Acholi against NRM/A incusions, and the destructive war waged by Joseph Kony’s army of mostly CI soldiers for control of Acholiland.

Chapter Two

Gwooko Dog Paco (Defending the Homestead), Cultural Devastation, and the LRM/A

As a little child growing up in Pamin-Yai, I acquired an education about moral issues and social responsibilities through ododo, folktales that were taught around wang-oyo, the evening bonfire. Some of my favourite stories were about Obibi, the human-eating ogre. In the gathering twilight, trees took on forms of giants, and the cacophonous screeching of night birds sounded like the laughter of devilish creatures up to no good. I imagined that Obibi was waiting in the blackness of the night to gobble me up.

Luckily for me, as illustrated in the collection of Acholi folktales by Alexander Mwa Odonga (1999) under the title Ododo pa Acoli. Vol. 1, the same happy outcome was expected in every Obibi story whether it was about obibi lawange acel, the One-Eyed Ogre, or the most terrible of them all, obibi lawange apar, the Ten-Eyed Ogre. The monster is always slain by the warriors. In one such story, a village maiden named Akello, her mother, Min Akello, and the rest of the family are living through a particularly bitter famine that had ravaged the land. Facing certain starvation, Akello and Min Akello discover that Obibi has plenty of food in his large well-tended garden. Akello and her mother resolve to steal some of that food. The theft goes on for a time until, one day, the thieving duo are caught red-handed by Obibi, who takes them as prisoners. The following day, Obibi demands that Min Akello cook Akello for dinner. But, while Obibi is away during the day, a leper whose acquaintance the pair had made prior to their captivity suggests that Min Akello instead cook an animal skin. Upon returning home that evening, Obibi sits down to a meal he believes is Akello. He grumbles that the meat is tougher than previous human meat he has eaten, but, still believing this was Akello, he eats the skin for dinner. Akello, meanwhile, escapes back to her village.

The next day, Obibi demands that Min Akello cook herself for dinner. As before, she conspires with the leper by preparing the skin of an animal for Obibi’s dinner. But as Obibi, grumbling, eats the tough meat, Min Akello, who is hidden inside a granary, makes some noise, thereby alerting the monster to her presence. Obibi at once realizes the trickery and begins chasing Min Akello as she escapes back to her home. While running, Min Akello begins to sing. The wind carries her voice to the village, alerting the community of the impending danger. Young warriors in the community rally with spears. On the outskirts of the village, the warriors meet and slay Obibi. They then cut off one of Obibi’s toes and use it to beat a drum whose magical qualities allow all the victims hitherto devoured by the evil Obibi to return back to life. The village is saved.

Gwooko Dog Paco as an Acholi Ethnocultural Identity

The ododo, like the one about Obibi and Akello’s family, resonate among the Acholi today because the stories illustrate and express a central part of the Acholi ethnocultural identity as lu-gwok dog paco, which, translated word for word, means lu (those), gwok (defend), dog (mouth), paco (homestead), or ‘those who defend the mouth of the homestead’ or engage in the act of gwooko dog paco (defending the homestead). Implicit in the concept of gwooko dog paco is the Acholi belief in communal responsibility whereby the people rally to defend the homestead when the oduru (alarm) is raised to signal an attack under way. This belief, with its emphasis on self-preservation, is not unique to the Acholi but rather can be found among any identifiable group with shared identity and cultural traits, not only in Uganda but in the African continent as a whole and indeed throughout the world.

The ethnocultural attitude of a particular group is shaped by its historical experiences, and in time that attitude determines the manner in which the group views and portrays itself in a multi-ethnic community. It establishes ‘the extent to which an individual or group is committed to both endorsing and practicing a set of values, beliefs and behaviors which are associated with a particular ethnocultural tradition’ (Marsella, 1990, 14). Thus, for the Acholi as for many African ethnicities, defending the home against threats that include but are not limited to wild animals, invasion by cattle rustlers, and inter-clan and ethnic warfare is an integral part of who they are as individuals and as a collective. In every Acholi household, the menfolk keep at least several tong (spears) for the protection of the family and, at a moment’s notice, when the oduru is made, every able body adult, usually men, can be relied upon to respond to the general threat facing the community because everyone subscribes to the notion of gwooko dog paco.

The Acholi’s particular concept of gwooko dog paco is rooted in the pre-colonial metamorphosis from fragmented Luo chiefdoms into present-day Acholi ethnicity. The collectivization of Luo chiefdoms into larger polities was born of the necessity for survival. According to R. Atkinson (1989), ‘being part of a larger group provided at least potentially greater security in times of danger or disaster. Other benefits included larger groupings of closely associated village lineages with which to hunt, go on trading expeditions, or exchange women’ (15). But, unlike such empire builders as Shaka1 in southern Africa, Sundiata Keita of Mali,2 or, closer to home, Mtesa I,3 the king of Buganda to the south of what became Uganda, the Luo did not keep a standing army for imperial purposes. Rather, faced with a common threat with potential to destroy the community, young men were mobilized. At such times, a defensive war was not only permissible but a matter of duty: every able-bodied youth was expected to dyeere (sacrifice) himself to fight the enemy in defence of the homestead.

To their sometimes allies and enemies, the Langi and the Alur, these predecessors of present-day Acholi were known as ‘Ogangi or Lo-gang, which was probably derived from Acholi word “gang,” meaning “home” or village’ (Ocitti, 1973, 8). As used, the description meant the ‘ones who stay home,’ likely a derogatory reference to the fact that, being mostly agriculturalists, the Luo rarely ventured beyond their ancestral homesteads. It could also mean that the Luo invested the defence of the homestead with lapir, a moral determinant of just wars that safeguarded against quixotic or opportunistic military adventurism. As explained by Acholi diplomat and former United Nations undersecretary for children and war Olara Otunnu, lapir is an unwritten Luo rule of engagement in times of conflict that was grounded in the notion of the just war, which required a ‘deep and well-founded grievance against the other side.’4

&nb

sp; The formalities of lapir required that the chief and a council of elders discuss whether or not to wage a war. Indeed, contrary to H. Behrend’s (1999) assertion that Acholi distinguished between lweny lapir, when ‘warriors set out to take women, cattle etc.,’ and lweny culo kwo, ‘war as a retaliatory measure after an attack by an enemy’ (39), a war was fought as a matter of necessity when all else had failed, and mostly as a pre-emptive or defensive act. The principles of lapir, in other words, did not authorize unsanctioned aggression against enemies for any reason, but they did sanction a pre-emptive strike against an enemy about to attack, defending the homestead during attack by the enemy, and engaging in hot pursuit while the attacking enemy retreated. Lapir did not permit the use of children and women in war, although there were occasional instances when the leader of a war party was a woman (Onyango-ku-Odongo, 1976).

The principles of lapir also required pre-colonial Luo states, when faced with a formidable opponent, to prefer diplomacy or temporary retreat, fighting only when absolutely necessary. Onyango-ku-Odongo (1976) recounts the story of Rwot Chua Omal, a successful Luo king who faced invasion from a neighbouring ethnic group in the mid-1600s. When the Tekidi settlement was attacked and ransacked, he ordered the community to build a defensive sanctuary in the mountains. Later, when a fearsome warrior tribe known as the Galla attacked the Luo settlement, Rwot Omal and his subjects strategically retreated to the mountain-top refuge. Unknown to the Galla invaders, the Luo had hauled huge stones to the top of the mountain and carefully positioned them at the mouths of the few paths leading to the hideouts. As the Galla warriors attacked, the Luo defenders rolled down the big stones, which crushed to death many of the invaders.

Thus, when Yoweri Museveni fought his way into power in January 1986, the Acholi had to choose between defending their traditional borders from the incoming NRM/A, which lacked the professional and national character that its successor, the UPDF, now has, or simply allowing the newly minted government free passage into the heart of Acholiland. The latter option seemed the least favourable to the Acholi, since the NRM/A’s ascension to power demonstrated that, in post-colonial Uganda, the mobilization, utilization, and legitimatization of non-state violence – including ethnic violence as state violence – was not only possible but necessary to establish ethnic hegemony. By ethnic hegemony, I mean the establishment of a particular ethnic character or dominant ideology over competing ethnicities or ideologies, usually by coercive force. M.S. McDougal and W.M. Reisman (1981) argue that, historically, international law involved a covenant among state elites which specified that only they had the right to regulate the use of coercive power. Private practitioners of coercion were tolerated if they sold their services to state elites by working as mercenaries.

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army