- Home

- Opiyo Oloya

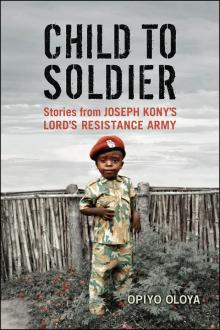

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army Page 8

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army Read online

Page 8

Despite some victories in the few months that it existed, the HSM was defeated by the NRM/A in October 1987, whereupon its volunteer recruits went back to their villages. After the failure of the HSM, the desperate and disparate responses to the threat facing the Acholi no longer followed established cultural norms, including the protection of children from harm. In conditions of severe stress, A. Honwana (2006) points out, disoriented individuals continue to perform what amount to culturally empty gestures denuded of the significance they once held before the disintegration of the vibrant culture. The absence of an overarching moral umbrella in times of war provides the opportunity for ‘anything goes’ because of the uncertainty over what is normal or abnormal, real and unreal, acceptable and unacceptable. Indeed, I contend, the demise of the HSM saw the beginning of a war which was cleverly disguised as gwooko dog paco but which in fact targeted those it purported to protect. The new phase in the war involved the forcible recruitment of children to be trained into soldiers. It was the beginning of one of the most heinous crimes against humanity perpetrated in modern times.

Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Movement/Army

In his book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, Jonathan Lear (2006) recounts the story of the native Crow Nation in the mid-nineteenth-century United States to explore the question of how a self-sufficient culture might respond when facing cultural devastation. Through the eyes of the last Crow chief, Plenty Coup, Lear traces events before 1850, a period that saw growing encroachment on Crow territory by white settlers:

Happiness consisted in living that life to the full. This was an active and unfettered pursuit of a nomadic hunting life in which their family life and social rituals could prosper. Because the tribe was threatened by other tribes, they developed a warrior culture to defend their way of life. The martial values – bravery in battle, the development of the appropriate character in young men, and the support of the warriors by all the tribe – were important constituents of happiness as understood by the Crow. (55)

By the turn of the century, the self-sufficient culture of the Crow was a mere shadow of its former self. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, and subsequent treaties with the U.S. government, ceded ever larger parts of the Crow’s traditional hunting ground. Lear highlights a statement attributed to Chief Plenty Coup: ‘But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened’ (2). After this nothing happened. To be sure, the Crow nation continued to exist on the reservations long after this date, but the very sinew that stitched them together as a people, that defined their way of life and, consequently, their very identity, had been broken. History, as the Crow knew it, had stopped once they resettled on the reservations. For Chief Plenty Coups, whatever happened after that could not be added to the autobiographical voices of the Crow because the Crow were no longer the nation they once were. As Lear points out, the Crow could have continued to fight the white settlers as other natives did, but Chief Plenty Coup saw his people’s hopes for survival as resting not on their ability to wage war with the whites but on their absorbing the whites’ knowledge to fashion a new existence separate and apart from the nomadic lifestyle the Crow had once known. This entailed thinking outside what the Crow were traditionally good at, fighting the Sioux and hunting buffalo, and reaching for something they had little knowledge of, diplomacy and peacemaking.

Following the defeat of the HSM, the Acholi, like the Crow, needed to come to terms with the NRM/A as the new power in the land and, for the most part, they did (Lamwaka, 2002). However, Joseph Kony, who fashioned his rebel movement along the same spiritual idea as the HSM, and initially on the premise of defending the Acholi, quickly demonstrated startlingly different strategies. The LRM/A in fact was less concerned with the survival of Acholi than with the creation of a huge area under its direct control. In the pursuit of this goal, the LRM/A made the Acholi, and indeed many other ethnic groups including the Lango and Teso, the target of its bloody campaign.

Virtually unknown before 1988, Joseph Kony was born in the early 1960s in a small village of Odek, about thirty-five kilometres east of Gulu town. His father, Luigi Abol, was a peasant farmer who also doubled as a Catholic catechist, and his mother was a homemaker. Kony had an unremarkable childhood, though he excelled at the Acholi laraka-raka (Nyakairu, 2008). He dropped out of school after sitting for Primary Leaving Certificate Examinations in 1981 (it is not known whether he passed).

Uganda’s economy in the 1970s and early 1980s provides further context for the dilemma that Kony’s contemporaries faced while growing up in rural Acholi. One of the recurring themes in the war in northern Uganda is the position of dispossessed Acholi youth who, feeling disconnected from the promises of the post-colonial era (Finnstrom, 2008), live lives of idleness. This is nothing new. For many of us who grew up in Acholi villages in the shadow of Gulu town in the 1970s, the most difficult aspect of our lives was not the persistent concern about the systematic killing of thousands of Ugandans, and especially the Acholi, by Idi Amin (Melady & Melady, 1977; Okuku, 2002), but the scarcity of goods in the shops, the absence of services, and the lack of job opportunities for school leavers. It was near impossible to get simple household items such as salt, soap, sugar, and medicine. Amin’s declaration of economic independence in 1972 saw many Asian traders and shopowners deported to Britain and Canada (Kuepper, Lackey, & Swinerton, 1975). Asians had performed the crucial role of linking peasants and the commercial industry, buying farmers’ produce such as cotton and tobacco for commercial sale and, in return, supplying the essentials needed by the peasants. Once the Asians were eliminated, their role was taken over by local businessmen, a few of whom became known as mafuta mingi, translated as ‘those who have a lot of fat [in their stomach].’ Many of the businesses, though, did not have the commercial connections and know-how to run shops. Consequently, long queues formed in front of shops as customers responded to rumours that an essential item was about to go on sale. Shops were otherwise mostly bare, with proprietors spending the day sitting around and doing little or no business.

When I travelled into Gulu town as a boy and young man, the mafuta mingi left me with a feeling of awe, even envy. They seemed to have it all – shiny new cars, beautiful families, and the good life. Children of the new rich went to the best schools in town and always looked smart in school uniforms and shiny black shoes. For the majority of Acholi rural children our age, in contrast, the day began with the family ritual of bayo lagot, literally, ‘throwing the hoe’ to till the field for cotton, maize, or another crop. Later, those lucky enough to be enrolled as students rushed home to wash themselves and eat angica, the cold leftover food from the previous evening, before dashing barefoot to the village school. It would be a lucky day if one had some food for lunch or some pocket money to buy a ripe banana or a stick of sugar cane to chew to deaden the sharp pangs of hunger.

To supplement family incomes, which came mostly from selling crops, our mothers, like most village women in rural Acholi, sold kongo arege, an illicit locally brewed gin. Often, most of the money went towards paying school fees, buying school uniforms, and paying for medicine. Gulu Hospital, the main government hospital, was located in town. Though patients were treated free of charge at the hospital, there were usually long line-ups and no drugs available. The better-equipped hospital was Lacor Missionary Hospital, located six kilometres west of Gulu town on Juba road. It was run by Canadian-born doctor, Lucille Teasdale, and her Italian husband, Dr Piero Corti.

Getting to town along the winding dirt road was quicker by automobiles, but cars were a rare sight in the villages. Some people had bicycles with carriers attached at the back which were used to carry heavy loads and passengers. Most people, though, used what the village wags referred to as bac pa Ladeny, ‘Ladeny’s bus,’ a reference to walking on foot. Sick villagers suffering life-threatening medical emergencies were often placed on the small carriages

on the backs of bicycles and slowly pushed to the hospital. Many patients often died en route. It was not unusual to see bundled-up corpses on the backs of bicycles being rolled back to the villages for burial.

The same bleak conditions persisted in the post-Amin era of the early 1980s under the second regime of Milton Obote, which failed to produce any significant changes to the political and economic fortunes of northern Uganda generally and rural Acholiland in particular. Kampala remained the centre of business and politics, and the trickle-down benefits for the rural districts were meagre. Corruption ensured that the basic infrastructure that had helped develop the Acholi economy in the 1960s, such as cotton ginneries and tobacco cooperatives, was never revived following the economic collapse of the Amin years. Poverty among youth of a certain age remained rampant as peasant farmers stopped producing for the export market, focusing instead on food crops that gave immediate financial returns (Kasekende & Atingi-Ego, 2008). Disillusionment became a part of the reality of those youth who had celebrated the fall of Idi Amin, seen as an oppressor of the Acholi, and had hoped for more under Obote’s second regime. There was nothing to do, and being educated did not guarantee a paying job.

When war broke out in 1979 as Idi Amin was pushed out of power, and again in the early months of the NRM/A invasion of Acholiland, the resulting breakdown of law and order created chaos for everyone; villagers and town people, rich and poor, faced the same uncertain future. And, although there is no hard evidence to suggest that this was the scenario that unfolded for Joseph Kony after the demise of the Holy Spirit Movement, it is conceivable that, with little or no prospect of finding steady employment in the skilled trades or in the service industry, a young man with a similar background to Kony’s might have seen opportunity in joining the insurgency, not to protect the homestead but for personal advancement.

This is not to argue that Kony was motivated by a desire to fight for the economic equality and dignity of all people, including the Acholi. It is meant only to provide a possible context for understanding how some Acholi youth of Joseph Kony’s generation, with very little formal education, might have taken up arms and then behaved so appallingly in the war that ensued.

Economic context, certainly, does not explain how a young Acholi with Kony’s background could rise to become such a prolific, and vicious, killer. For that, we need to examine the cultural devastation of Acholi at the time and the perfect cover it provided for a psychopathic mass murderer like Kony to build an elaborate army of terror that was large enough to commit transnational genocide.

The Evolution of the LRM/A

At least initially, after the collapse of the HSM, Kony seemed to be encouraged by some Acholi elders to keep up the fight against the NRM/A (Finnstrom, 2008). Following the NRM/A’s successful invasion of Acholiland in early 1986, remnants of the UNLA had crossed over to Sudan where it reconstituted itself as the Uganda People’s Democratic Army. One version of events suggests that Kony joined the local UPDA forces to fight the NRM/A in 1986. Another version has Kony joining Lakwena’s HSM, and himself becoming a spirit medium, or lakwena, possessed by several spirits, the dominant one named after a former army officer in Idi Amin’s regime called Juma Oris (Allen, 1991; Behrend, 1999; Dolan, 2009, 80). The most likely scenario is that, in the initial resistance against the NRM/A, the various groups united and disbanded when it suited their immediate goals. Kony likely associated himself with several groups at once while building his army into a viable force. What is clear is that, by the time HSM had fought to within a hundred kilometres of Uganda’s capital of Kampala before being defeated by the NRM/A, Kony had established a small largely ineffectual insurgent army which was fashioned as an offshoot of Lakwena’s HSM in Gulu district and which, for a short time, strategically appropriated the HSM name. The disintegration of Lakwena’s HSM provided Kony’s movement with much needed personnel when some of her supporters joined him. The insurgency then underwent a name change, calling itself the United Holy Salvation Army (UHSA) to reflect the absorption of the new group. But the movement was still mostly concerned with creating a moral dimension for the war against the NRM/A. Like its predecessor the HSM, the UHSA claimed to want to clean the Acholi people of the sins of which they were guilty (Behrend, 1999). This meant waging a holy war mostly against the superstitious faith healers known as ajwaka, and those deemed unholy (Behrend, 1999).

Likely in tune with the desperate social conditions of the Acholi people, and also with the paradigmatic appeal of salvation as a mobilizing ideology, Kony insinuated himself as the leader of the new resistance. By invoking the Lord’s name, and claiming to be fighting to restore the Ten Commandments, Kony positioned his movement to grow at the expense of the widely popular Alice Lakwena. The religious context was a means by which Kony could stake the purity of his lapir, the moral claim to wage a war. Like Auma’s Lakwena, Kony spoke of being sent ‘to destroy evil forces in the world’ (Behrend, 1999, 179). However, in the much discussed 1993–4 peace talks, Kony is also recorded on video saying that ‘land is wrested by spear,’ implying that war was a necessary weapon for forcefully asserting ownership over resources.

Furthermore, Kony exploited the Acholi’s antipathy towards those in the south and west to recruit for the insurgency. According to informants who spoke to me in Gulu, Kony channelled a high moral calling to fight off what he described dismissively as ‘Yoweri’s army.’ Notwithstanding that the Yoweri in question was the de facto president of Uganda, the founder of the LRM/A contemptuously saw him as an usurper of power, a carrier of opoko, the gourd used by cattle herders from western Uganda.6 In other words, rooting out the invaders, restoring the Lord’s commandments, and freeing the Acholi people from tyranny was a noble duty. Initially at least, a religious orientation provided Kony’s insurgency with the legitimacy it needed to continue to use violence in a space where violence was condemned. It also allowed Kony to distinguish his insurgency from other agents of violence, notably the NRM/A and the UPDA, both of which were accused of atrocities (Behrend, 1999).

The secularization of the UHSA began in early 1987 when, using force and persuasion, Kony began incorporating elements of the UPDA. In February 1987 he peacefully co-opted a UPDA unit commanded by Okello Okeno, persuading some officers to join him while taking those who refused prisoner (Behrend, 1999, 179–80). The biggest boost to the UHSA came in May 1988. The UPDA signed a peace accord with the NRM/A, marking the end of resistance by a force consisting mainly of professional soldiers. However, a breakaway group of thirty-nine soldiers, led by former UPDA commander Odong Latek, refused to surrender because of suspicion of NRM/A trickery, choosing instead to join Kony’s UHSA. The nomenclature arising from this alliance, the Uganda People’s Democratic Christian Army (UPDCA), reflected both the fluidity and the conflicted duality that characterized the early prototypes of the LRM/A. By claiming a democratic goal, Kony seemed to acknowledge the need to broaden the political and military coalition to fight the NRM/A. At the same time, he persisted in retaining the religious dimension that had marked Lakwena’s HSM.

The creation of the UPDCA as an insurgent force using conventional guerrilla strategies of hit-and-run transformed what was mostly an insignificant uprising with religious overtones into a rebel movement that focused on recruiting, training, and deploying its army against the battle-tested NRM/A. It also marked the escalation into a complex transnational insurgency war that would later straddle Uganda and Sudan at the beginning, and move into the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the Central African Republic (CAR) at a later stage. The key reason for the metamorphosis of the insurgency into a rebel movement that was finally recognized as a threat in northern Uganda seemed to be Kony’s ability to network and make deals with other forces. His group succeeded in linking up with some former Amin soldiers who operated under the West Nile Battle Front (WNBF), led by the aforementioned Juma Oris. Some time between 1991 and 1992, the UPDCA became the Lord’s Resistance Army.

Given the superior

force deployed by the NRM/A in consolidating its hold over Acholiland, one could speculate that the choice of name was a deliberate attempt at one-upmanship in which the ‘Lord’ in the Lord’s Resistance Army was arguably more fearsome and omnipotent than the ‘National’ in the National Resistance Army. In any case, it betrayed the persistent appeal of religion as a mask for the war that Kony wanted to fight. More important, it also showed that Kony would do anything in order to come across as a credible opposition to Yoweri Museveni, even though his rebels early on were less focused on defending the Acholi people against an attacking army than on achieving power.

Children into Soldiers: The New War

At the height of the insurgency between 1996 and 2006, Joseph Kony’s LRM/A used thousands of child-inducted soldiers on the front lines in southern Sudan and northern Uganda. By then, the LRM/A had become a formidable killing machine that wiped out entire villages, as happened on the night of 20 April 1995, when it murdered in cold blood over 240 people in Atiak on a single day (Justice and Reconciliation Project, 2007). This was followed by the Mucwini Massacre in the early morning of 24 July 2002, when fifty-six women, men, and children were murdered (Justice and Reconciliation Project, 2008), and the Barlonyo Massacre on 21 February 2004, in which over 300 civilians were murdered (Justice and Reconciliation Project, 2009). It should be pointed out, that prior to these well-publicized mass murders and throughout the period, the LRM/A killed and maimed thousands of civilians in northern and eastern Uganda, and in southern Sudan, usually in small numbers. Culturally, these mass murders and the forcible displacement of over 400,000 Acholi into camps left the population shell-shocked (Human Rights Watch, 2003a, 2005). Internationally, the killings led to the indictment of five senior LRM/A commanders, including Joseph Kony, by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity (ICC, 2002; Lee, 1999).

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army

Child to Soldier: Stories from Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army